|

| |

|

ACTUAL

EXHIBITION

|

Gary Auerbach

NATIVE AMERICAN

From

july 13 to August 11 2002

Exhibition Essay

Images

Made to Last

Platinum Portraits

of Native Americans by Gary

Auerbach

By Maricia

Battle

Curator,

Prints and Photographs

Division, Library of

Congress

While it

is difficult to change

careers in mid-path, we are

appreciative because it

brought Gary Auerbach to

photography, an art form he

both treasures and for which

has true passion. Before

becoming a photographer,

Auerbach was a chiropractic

doctor. As a result of a

hand injury in 1989,

Auerbach put aside his

chiropractic practice, and

turned his attention full

time to what had before been

an earnest hobby.

His work

with cameras in his practice

gave him a natural

familiarity with both large

format cameras and film

characteristics, and his

compassion for the human

subject, made portraiture a

natural progression. He uses

an 8x10 and an 11x14 view

cameras, not your average

large format equipment. But

what further distinguishes

him from other photographers

is his technique of contact

printing the image with

platinum metal salts, which

increases their tactile and

textural luster while

creating an important

archival photographic

record.

American Indians, an

integral part of American

history, have been

represented in the works of

many photographers since the

dawn of photography. James

E. McClees, with Julian

Vannerson and Samuel Cohner,

produced some of the

earliest Native American

images in studios in

Washington, DC in the late

1850s, later joined by the

works of Charles Milton

Bell. Most of this early

work consisted of staged

images of American Indian

dignitaries during their

visits to the Capitol. In

the 1890s, John Hillers and

John Grabill produced some

of the first survey images

of American Indians in their

own environment. It was not

until the turn of the

century that the most

recognized and celebrated of

all the photographers,

Edward S. Curtis, begin his

thirty-year project of

photographing Native

Americans in natural

settings.

Our

curiosity about others and

ourselves has always been an

underlying issue in most

documentary photography. In

light of recent events, that

need to know has resurfaced

with a vengeance. Unlike

earlier anthropological

studies, Curtis seemed able

to rise above the physical

examination of the American

Indian culture to get inside

the soul of the people.

While not an insider, his

camera focused on the

individuality and the

essential humanity of his

Native America subjects.

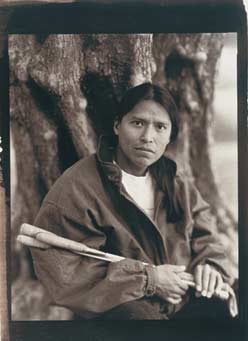

The same

can be said of Gary

Auerbach's images. He

captures the dignity and

strength of the Native

American culture. He allows

the subject to get

comfortable, to know the

lens and the eye of the

camera in a way that is

clearly non-threatening. It

is said that the eyes are

the windows to the soul, and

you know from looking at

these images, that the

individuals photographed are

at ease with both the

photographer and the camera.

This is not an easy

undertaking, given the

private nature of the Native

Americans. The resulting

images are photographs that

possess the ancestral

qualities Curtis discovered

in his subjects - the heart

of the people.

With

Auerbach’s sensitivity to

the Native American culture,

permanence is clearly a

defining issue. Gary has

explored various printing

methods, and in the

tradition of Curtis, he uses

the precious metals,

platinum and palladium, to

contact print each image.

Each of the photographs in

this collection is

hand-coated with these

metals etched into archival

watercolor papers, ensuring

the permanence of the print

for hundreds of years. A

by-product of this method is

that the photographs have an

ethereal quality, with

unmatched dimension and

depth.

Only time

will tell if Auerbach will

emulate Curtis’ effort to

the degree of producing a

thirty-year masterwork of

American Indians. I do know

he will continue to develop

this body of work because it

is his passion. And with

passion, and expertise,

comes what we call, a work

of art.

|

Introduction

John A. Ware, Director Amerind

Foundation, Inc. Dragoon, Arizona

|

The

Amerind

Foundation was

established in

1937 by

William

Shirley Fulton

who, in a

lifetime of

collecting,

amassed one of

the finest

assemblages of

American

Indian art and

material

culture in the

country. The

collections

were greatly

expanded and

their temporal

span enlarged

by

Amerind-sponsored

archaeological

excavations in

the

southwestern

U.S. and

northern

Mexico in the

1940s through

1970s. When

the Amerind

Museum opened

to the public

in 1987 (prior

to 1987 the

collections

could be

visited only

by appointment)

the

collections

were

especially

strong in the

late

prehistoric

(pre-1540

A.D.) and

historic

periods (post

1540 to 1900).

|

When

exhibiting and

interpreting

such

historical

material,

there is

always the

risk that

museum

visitors will

walk away with

the impression

that American

Indians are

part of

America’s

past but not

its present

and future. In

fact, it has

been argued

that museums

shoulder much

of the

responsibility

for conveying

the impression

both at home

and abroad

that Indians

died out with

the buffalo;

that although

some Indians

may still

exist in the

Southwest,

Oklahoma, and

perhaps South

Dakota, their

languages,

world views,

belief systems,

and most other

aspects of

their

traditional

cultures have

been lost,

except for

what museums

have managed

to preserve.

Contrary

to these

impressions,

there are

perhaps as

many people

who identify

themselves as

Native

Americans

today at the

dawn of the

twenty-first

century as

there were at

the close of

the fifteenth

century when

Europeans

first set foot

on the shores

of the

"New

World."

In other words,

despite five

centuries of

invasion,

displacement,

marginalization,

and the

impacts of

European-introduced

diseases,

American

Indians are

still very

much here! In

the words of a

Zuni friend,

"we are

here, now, and

always."

The

photographs of

Gary Auerbach,

friend and

neighbor of

Amerind who

divides his

time between

his studio in

Tucson and

pistachio

orchard in

Dragoon, are a

perfect

antidote to

the "old

Indian things"

that occupy

museum shelves

in

anthropological

museums across

the country.

Gary’s

splendid

platinum

photographs

show American

Indians as

they are today:

friends,

neighbors,

doctors,

parents,

daughters,

sons, poets,

painters;

thoroughly

modern

Americans with

modern

interests and

concerns, but

with a

connection to

past and

tradition that

is palpable

through the

lens of

Auerbach’s

giant camera.

The

Amerind is

pleased to

bring these

images of

contemporary

Native America

to its

audience, in

both this

catalogue and

the exhibition

of Auerbachs

prints at the

Fulton-Hayden

Memorial Art

Gallery at

Amerind. We

thank Gary

Auerbach and

his subjects

for their

vision,

Darlene Kryza

for her design

and Linda

Vidal and John

Davis at

Arizona

Lithographers

for their

production of

the catalogue.

|

|

|

F O C A L E

Place du Château, 4

CH-1260 Nyon

Tél/Fax++41 22 361 09 66

focale@focale.ch

|

|

|